It was a manifestation of immense colonial hubris—one of the most expensive public works projects of its day, an architectural marvel built on the backs of those it would incarcerate. It was also the scene of brazen escapes, of riots with tragic outcomes, and often unspeakable cruelty of the prison experience. For nearly 180 years, Kingston Penitentiary would serve as Canada’s oldest and most notorious prison, incarcerating men, women, and children.

Grace Marks, a 16-year-old Irish immigrant, the first women to be convicted of murder in Upper Canada, and the inspiration for Alias Grace, a novel by Margaret Atwood, was imprisoned in the Kingston Penitentiary from 1843 until 1872.

Marie-Anne Houde, convicted of murdering her stepdaughter, Aurore Gagnon, was also held here until 1920 after her death sentence commuted. She remained in the Kingston Penitentiary until 1935.

Kingston Pen also housed “go-boys”—prison slang for those who manage to escape. The slang is referenced in former prisoner Roger “Mad Dog” Caron memoir called Go-Boy! Memories of a Life Behind Bars, which would go on to receive a Governor General Award for non-fiction in 1978.

Caron once said of his incarcerated life, “I lived in a jungle. I survived in a jungle. Every conceivable thing that could be done to a person in prison happened to me.”

Author Michael Ondaatje used the Pen as a site from which his fictional Caravaggio escapes in the Novel In the Skin of a Lion. But a number of prisoners successfully escaped the Pen in real life, like Norman “Red” Ryan, who broke out in 1923, and Ty Conn, who escaped in 1999.

“Kingston Penitentiary bares the extremes of the human experience: death and life, fear and hope, confinement and solitude – we try to shine a light on that world,” says Cameron Willis, former Operations Supervisor and Research Assistant at the award-winning Canada’s Penitentiary Museum, which dedicates itself to the preservation and interpretation of the histories of Canada’s federal penitentiaries.

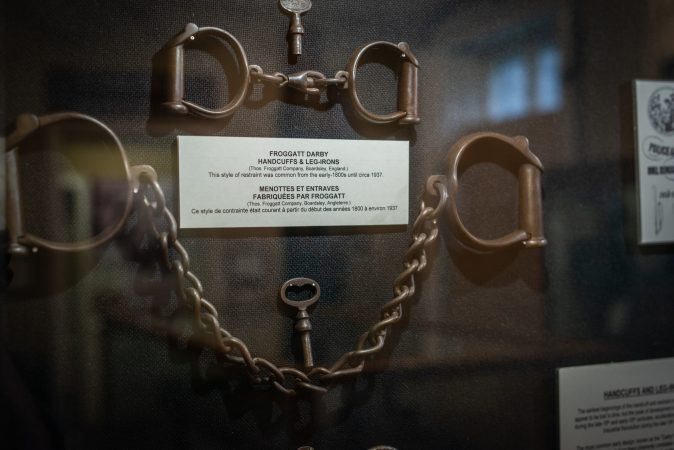

Lodged within Cedarhedge, the stately home that once served as residence for the warden of Kingston Pen, the museum exhibits were originally based on a small collection of contraband items assembled in the 1950s and 1960s and historic documents saved from the scrapheap during the same period by conscientious officers of Kingston Penitentiary. Canada’s Penitentiary Museum today houses eight rooms devoted to art created by incarcerated persons, prison industries, escape paraphernalia, contraband, and uniforms from the course of the prison’s history.

Kingston Penitentiary predates the Canadian confederacy in 1867, designed, built and opened in the twilight years of Upper and Lower Canada. A halfway point between Montreal and Toronto, Kingston was selected to house the prison as it had access to the waterfront and limestone.

“Kingston Penitentiary is a beautiful piece of architecture, built in a neoclassical-inspired design – partially designed and supervised by William Coverdale, who was also behind Sydenham Street Church and City Hall in Kingston’s Market Square,” explains Willis. The first cell block – which has stones marked 1833 – was also built by over a hundred-day labourers, some who had worked on the Rideau Canal. But the rest of the penitentiary was built with prison labour – an incredible fact in itself.”

“Kingston Penitentiary set a template for the rest of the development of the federal prison system, serving as the model, not only in terms of its architecture, but in the intangible human elements that created the system: the rules and regulations, the way in which prisoners were treated, the way they were dressed, the discipline of the guards. All of this informed the new federal prisons that were opened after Confederation across Canada,” he continues.

Willis, who has investigated and studied the lives of incarcerated persons over the course of Kingston Penitentiary’s history, adds that, depending on the time period, some in Canada’s cultural mosaic—Irish, Italian, or Eastern European immigrants at one time, and Indigenous Black and French Canadians at another—have been overrepresented in the prison population, the result of broader prejudices and inequities in Canadian society.

“During the 19th and early 20th centuries, for example, Francophones in Ontario were reputed to be more criminally inclined than Anglophones,” explains Willis. “The museum collection includes a report from 1862 where Warden Donald Aeneas MacDonell claims that French Canadians are a duplicitous and untrustworthy bunch, expressing his concern that they were tricksters and could not follow discipline.”

Roger Caron was perhaps the most famous Franco-Ontarian incarcerated at Kingston Penitentiary. Caron spent much of his adolescence and adult life in Canadian reformatories, jails, and prisons. He captured the tragedy of Kingston Pen’s 1971 riot, which had documented in Bingo! The Horrifying Eyewitness Account of a Prison Riot.

“The 1971 riot was front page news for many days – it started with the hostage taking of six officers, it lasted five days and resulted in the death of two prisoners,” says Willis. “During the riot, much of the prison was destroyed. We still have the broken bell that was used to bring prisoners to and from their cells and workplaces. It had been there for 50 years, a symbol of an earlier time period – and when it fell, it was in some ways the symbolic death knell of what was left of the old penitentiary system.”

Over the course of its history, conditions at Kingston Penitentiary would spark prison reforms—despite Charles Dickens praise, who in 1842 described the prison as “admirable” and “humanely run.” It was just a few short years, however, before the prison documented the repeated corporal punishments inflicted on eight-year-old Antoine Beauche, the youngest prisoner on record at the penitentiary, for “offences of the most childish character,” and the flogging of Alex Lafleur, 11 years old, for speaking French.

The Brown Commission a, “scathing indictment of inhumane treatment” by politician and Toronto Globe editor George Brown 1849, also catalyzed reform, but real change was slow. It took further advocacy on the part of Anges MacPhail, Canada’s first female Member of Parliament, who was moved to action after news of a prison riot at Kingston Pen in 1923. MacPhail saw first-hand the deplorable conditions at the penitentiary and worked for further reform throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

“The strict discipline and severe conditions were often justified by administrators, the press and members of the public by reference to the “dangerous and desperate characters” who ended up behind its walls – that’s quoting from a 1907 article in The Ottawa Citizen,” says Willis. “But it was also a site, in common with other federal prisons in the 1950s and 1960s, where prisoners organized activities, like sports, concerts, newsletters, even a radio show – and the Museum features exhibits on these subjects.”

Willis says his favourite room is the museum’s exhibit of historic and contemporary art by the incarcerated, often praised by museumgoers. “In general, the closure of Kingston Penitentiary in 2013 and the subsequent walking tours have greatly increased interest in its history, and in the number of visitors coming to the museum.”

“What was once a maximum-security federal prison has been transformed into a place – one hopes – of learning and discovery,” he says. “Canada’s Penitentiary Museum continues to help the public learn from the past to better inform our present and our future.”

The Penitentiary Musuem is opens May to October, 9 am to 4 pm. For more information visit their website. Kingston Pen Tours from May to October. Tickets are available online.