History in motion at Kingston’s PumpHouse Steam Museum

Read the French version on our French website

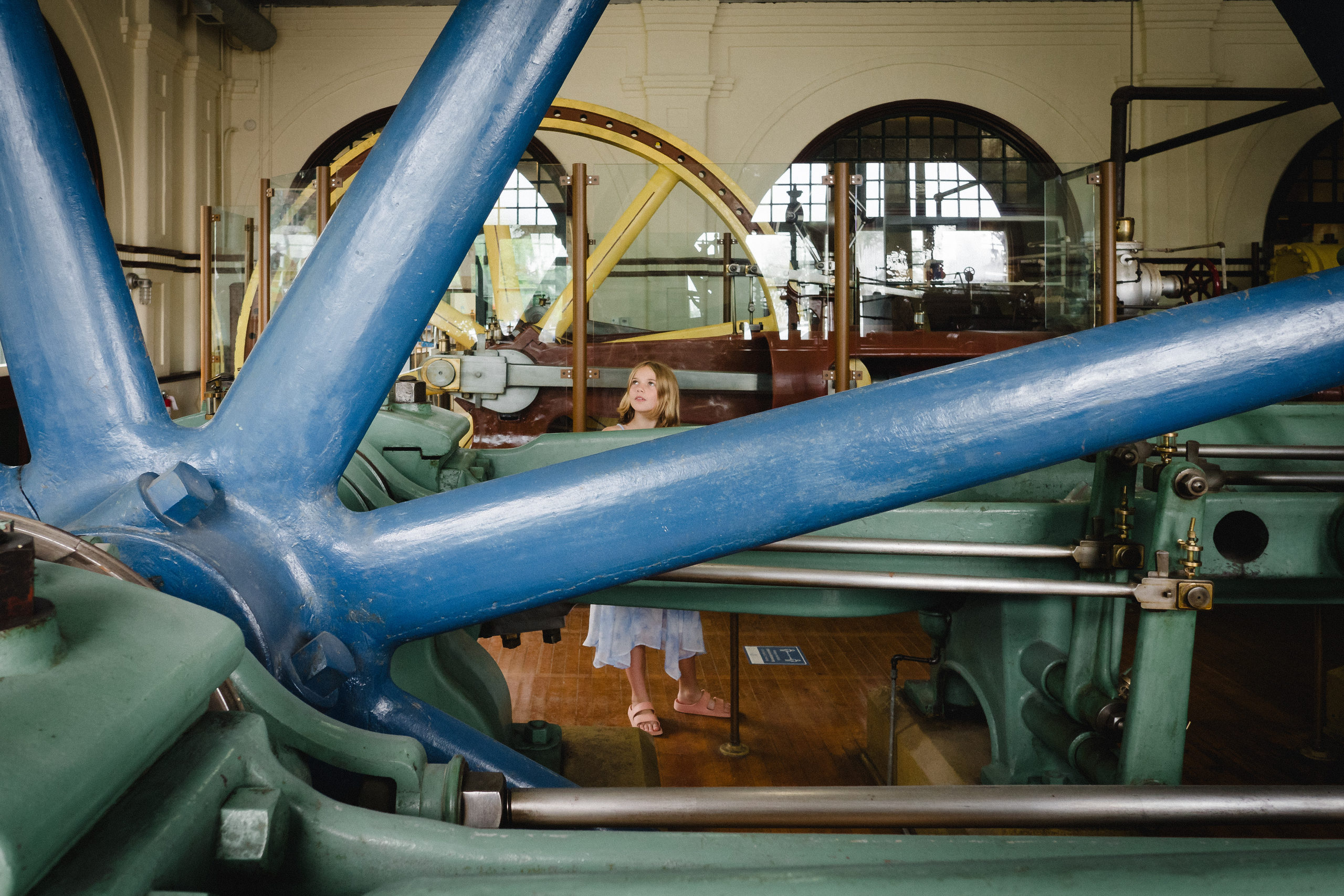

It is a story of disease. Fire. And water. Of an emerging young city fueled by its ambitions to become a budding metropolis in the era of a nascent nation. A story embodied and preserved in Kingston’s PumpHouse Steam Museum, a magnificent building that today tells the story of how water transformed the fortunes of the Limestone City.

Perched at the junction between the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, Kingston boasts one of Canada’s oldest original water works – one of only six similar preserved water pumping stations remaining in North America – where steam-powered pumps provided the first running water to Kingstonians for over a century.

This is truly history in motion.

The PumpHouse Steam Museum is housed in a majestic building known for its Richardsonian Romanesque architectural style typified by heavy rusticated stone and heavy horizontal lines that can still be seen inside parts of the museum. The building was designed by John and Joseph Power, a prolific father-son architecture duo.

“Inside the PumpHouse, you could actually see these beautiful, massive industrial Victorian-era pumps working their way through and pumping the water out to the city,” explains Melissa Cruise, Acting Supervisor of Heritage Services for the City of Kingston. “There was a lot of thought behind it, which today, you know, we don’t always see that level of thought going into very heavily industrialized buildings.”

In an era where Canada’s capital hopscotched from Montreal, Toronto, Ottawa and Kingston, the PumpHouse was critical to keeping Kingston in the running as the capital of an emerging country. Kingston had to demonstrate that it could offer its growing citizenry safe and healthy drinking water, eradicate disease, and fight the calamity of city fires.

“We see a few things begin to occur,” adds Melissa. “In 1840, a massive, devastating fire rolls through the city. And unfortunately, there was no centralized pumped water station – so in terms of an early fire brigade, we’re seeing people using bucket brigades and the occasional pump truck.”

“Over the course of the 19th century, Kingston would also see three severe outbreaks of cholera caused by contaminated well water, including a devastating outbreak in 1834 that would kill 1 in every 16 Kingstonian.”

“The first iteration of the city of Kingston Water Pumping Station was actually independently owned and operated – and their priority wasn’t necessarily to provide clean drinking water to ordinary citizens,” says Melissa. “One of the reasons the PumpHouse actually came to fruition is that the city had a handful of very wealthy landowners whose insurance rates were going through the roof because of the fires – and a centralized water pumping would help lower those rates.”

“We have really amazing archival records pertaining to the museum that are sitting in the city of Kingston archives at Queen’s University,” adds Melissa. “And so we’re able to actually go through all the correspondence and see city officials imploring this independent business to start to lessen water rates so more people can access and make something that can actually support a growing, healthy society.”

Though it is a marvel of the history of water in Kingston, the PumpHouse Steam Museum has also established itself as a cultural crossroads, hosting extraordinary exhibitions.

In the summer of 2023, the museum hosted The Art of Survival, an art exhibit in collaboration with the Prison for Women Memorial Collective, curated from coast to coast in Canada by artists who were formerly incarcerated, showcasing their creations, hosting sharing circles, and advocating for those who lived and died inside women’s prisons across Canada.

The museum’s newest exhibition is The Stuff Stories Are Made Of, its never-before-seen objets d’art pulled from collections that belong to the City of Kingston Heritage Services. The exhibition is now open and runs to the end of May 2024.

“It will be a really phenomenal exhibition that we’ve curated in-house,” explaims Melissa. “We’ve been able to go in and have a look and cherry-pick the things that we haven’t necessarily been able to pull out for exhibitions in a while that are just really interesting, or really fun, or really neat, or just incredibly odd.”

“It’s all about looking at what we collect and looking at turning it on its head. We’re not necessarily displaying things in a very traditional, austere manner. We’re actually treating a lot of our historic objects more like art pieces.”

“For instance, it’s the summer of Barbie and, oddly enough, we have a Barbie and Ken in our collection, so we’re pulling them out in tandem with everything” she concludes. “We also have beautiful stone cut prints – including one by Pudlo Pudlat called Umingmuk.”

“Every single one of our exhibitions is bilingual,” adds Melissa. “Whether the exhibition is produced in-house or we’ve borrowed it from another site, it must always be available in French. Full stop. We also try to make French-language tours available for each one of our exhibitions.”

Although the PumpHouse Steam Museum focuses on the history of water in the city of Kingston, the museum is also committed to the future and to the protection of this natural resource made vulnerable by human activity.

The museum, housed in the traditional homeland of the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee and the Huron-Wendat, has engaged in the protection of water, supporting Water Warrior programs and working with Engineers Without Borders to establish some of these programs.

“These impactful programs speak to water quality and security,” underscores Melissa. “They give young people an opportunity to really think about what it means if they don’t have water security.”

As it educates, enlightens and enchants its visitors, the PumpHouse Museum tells a story – one about the life-giving force of safe and clean drinking water.

This is the stuff stories are made of.

“There is joy in telling Kingston’s stories through the museum,” concludes Melissa. “And that’s really what it boils down to. It’s about telling stories. Preserving stories. Getting people excited about these stories – because they are really relevant today and can help guide us in caring for water.”